RADIO'S FIRST VOICE , , ,

The first radio broadcast ever in the world's history was made by Reginald Fessenden on Christmas Eve 1906 when he beamed a "Christmas concert" to the astonished crews of the ships of the United Fruit Company out in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Beamed out from the 400-foot towers of the transmitting shack at Brant Rock, Massachusetts on the Atlantic coast, this program commenced exactly at 9 o'clock, with 'CQ CQ CQ', meaning general call to all stations within range', sent out in dots and dashes. Then, over the microphone, Reginald himself gave a brief speech as to the program to follow. This was immediately followed by one of the operators switching on the Edison phonograph and a solo voice singing Handel's 'Largo'. The first case of "mike fright" I was registered when Mr. Stein, an assistant, backed away unable to utter a word! However, Fessenden grabbed his violin and 'fiddled' through 'O Holy Night' . singing as well as playing. Helen, his wife and his secretary, Miss Bent, endeavored to read parts of the Bible text, 'Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace to men of good will', but, like Mr. Stein, they suffered stage f right. Concluding the program, Fessenden wished his listeners "A Merry Christmas". The success of this first broadcast was verified by operators, not only from those on the ships of the United Fruit Company but also from vessels all over the south and north Atlantic, amazed at the magic and miracle of this first wireless radio broadcast. A Brief

Biography of In his early days at school he showed remarkable aptitude in mastering mathematics, languages and music. He graduated to Trinity College, Port Hope, with honors. His next step forward was the offer of further tuition together with a paying mastership at Bishop's College, Lennoxville. This was followed by an offer of a teaching position in Bermuda which he successfully fulfilled. For many years a subscriber to and avid reader of the "Scientific American", Reginald also kept a scrapbook crammed with news clippings relative to all the inventions of Thomas Alva Edison. His constant studies furthered a determination to make the voyage from Bermuda to New York to seek an interview with the famous inventor and, possibly, a position. The fact that Edison was too busy to interview him at his laboratory did not deter young Fessenden. Haunting one of the Edison installations in New York, he virtually 'got in through the back door'. An instrument tester had just walked off the job. The foreman offered the position to Fessenden and he soon became chief tester. In this capacity he gained further knowledge and practical experience both inside and out as he was frequently called out as electrical 'trouble shooter'. Many wealthy men had their own private generating plants. A breakdown in the dynamo or fire in the wiring, as occurred at the mansion of financier J. Pierpont Morgan, meant a call for Fessenden to end the darkness. Mr. Morgan was so pleased to have the power restored that he gave Fessenden a liberal reward for his services and asked him to inspect the wiring. The wires in use were bare and Fessenden suggested replacing them with wiring covered with rubber insulation and encased in galvanized tubing. He later improved on this principle in the Edison chemical laboratory. When word of the skilled work that Fessenden was performing reached him, Mr. Edison told Mr. Kreusi, the plant foreman, that he needed Fessenden as his assistant to carry out experiments on generators and to develop a rubber insulation for conducting wires at the main Edison plant in New Jersey. The New Jersey plant was at the time considered to be the finest experimental laboratory in the world. With access to a huge library and the use of all equipment in the Weston instruments building, Fessenden developed more inventions including some of his own. I n 1890, after two years, he was elevated to the post of chief chemist. During this period he met men of great renown in the scientific world . . . . Lord Kelvin, Dr. Kennelly, George Westinghouse, the inventor of air brakes for trains. Realizing his worth, Mr. Westinghouse offered Fessenden the position of supervisor of work on generators and the improvement of electric light bulbs in the laboratory of the Westinghouse plant at Newark, New Jersey, as well as his work at the Weston instrument plant. By designing new lead-in wires for the bulbs, Fessenden soon solved Mr. Westinghouse's problems enabling him to fulfill his contract to light the huge Columbian Exposition in Chicago. After solving other urgent problems Fessenden visited England where, at Newcastle-on-Tyne, he observed the operation of the newly invented steam turbine of Charles Parsons. Fessenden remarked on the great possibilities of applying the steam turbine-electric drive to propel ships of all sizes . . . another prediction which has come true. On his return from England, Fessenden found a teaching appointment awaiting him at Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana. As Professor Fessenden he was given a free hand by the University principal, Dr. Smart, to purchase all necessary equipment. He was thus enable to conduct laboratory experiments furthering his cherished ambition, the development of sound vibration and transmitting sound without wires. At the end of the school year Professor Fessenden, much to the regret of the trustees and students, decided to leave Purdue in order to devote all his time and energies to developing his own inventions. However, he received a letter from George Westinghouse with which was enclosed one thousand dollars, but with the stipulation that the Professor come to Pittsburgh. Accordingly, Fessenden, with his wife Helen and their only son, Reginald Kennelly Fessenden, moved to a fine comfortable home on the outskirts of Pittsburgh. While engaged in further research, Fessenden developed and patented some of his own inventions, one of which, microphotography, is of great importance today and is used by banks and business concerns as well as libraries and other professional institutions throughout the world for 'mini-recording' of cheques, documents, etc. Following an impressive demonstration of his improved telegraph system to the United States Weather Bureau in Washington, Fessenden was employed at a salary of $3,000. yearly and furnished with a testing station and aerial masts at Cobb Island in the Potomac River. Bureau chief and officials were astounded when Fessenden transmitted his signals without wires from Cobb Island to Arlington, Virginia, a distance of 50 miles. However, it was the transmission of speech, not "dots and dashes", which spurred Fessenden to greater effort. Toiling day and night, he cut almost microscopic incisions into a phonograph cylinder in order that his interrupter would break the circuit 10,000 times each second. At the first trials voice sounds were unintelligible, but after persistent effort Fessenden was rewarded by performing the first miracle of transmitting the human voice without wires even though it was over the short distance of one mile.

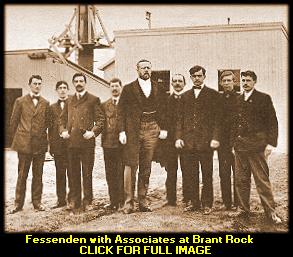

On renewal of his contract for two years, the U.S. Weather Bureau decided to enlarge the scope of their activities by building new stations and three high aerial towers at Roanoke Island off the Carolina coast, to which Fessenden moved. Additional towers were built and with improved equipment and competent workmen, long distance code signals were transmitted. Rather than be tricked out of his inventions, Fessenden resigned. Hearing of the inventor's technical ability, two Pittsburgh millionaires, Walker and Given, agreed to form and finance a company, the National Electric Signaling Company, employing Fessenden on condition that he place his inventions in the name of the Company. Two wireless stations were built at Brant Rock, Massachusetts, with 400-foot antenna towers and the latest equipment installed. As a result of their excellent performance, three more stations were build in New York, Philadelphia and Washington. These Fessenden installations were the first to send wireless dot and dash messages overland, establishing a record 6,000 miles, even to Alexandria, Egypt, one quarter of the way around the world. For the United Fruit Company, Fessenden had established wireless stations in New Orleans, on their ships, and at their plantations in Guatemala. Best of all, he had beaten Marconi by transmitting Morse code in both directions across the Atlantic. In Canada, by Special Act of Parliament, the Fessenden Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada was created with such prominent men as Sir Frederick Borden serving on the Board of Directors. Fessenden was also called to a formative commission meeting relative to harnessing the enormous potential power of Niagara Falls, but his ideas proved too advanced for acceptance by Adam Beck and others.

Spurred on by this success, Fessenden improved the efficiency of his high frequency alternator and with a new type of umbrella antenna of his own design, both stations were in regular communication. In June a small testing station had been built at Plymouth, eleven miles from Brant Rock, with Fessenden conversing regularly by voice between the two stations. In November a letter was received from Mr. Armor containing the astounding news that instead of dots and dashes he had clearly heard the complete conversation of Mr. Stein at Brant Rock telling the operator at Plymouth "how to run the dynamo". Thus the first human voice to be transmitted across the Atlantic was that of Mr. Stein. On Christmas Eve, Fessenden and his assistants presented from Brant Rock station the world's first broadcast by radio. The program was successfully repeated on New Year's Eve. 1906 was a memorable year for the inventor himself. To speed up operations in and around the station, he had invented the 'beeper' or signal from Fessenden, and which was fitted to his workmen's hats. This device later proved to be of great value. (Had a 'beeper' been operating aboard the mercy plane which was lost recently in Canada's Northwest Territories with the resultant loss of three lives and injury to the pilot, the tragedy might possibly have been averted.) Following the sinking of the Titanic by collision with an iceberg in the Atlantic, Fessenden stated that he had "bounced signals off icebergs by radio, measuring the distance". His invention was really the forerunner of the present-day radar. His patented invention of the Fathometer proved of great value in measuring the ocean depths. This device was of great assistance to the Allies during World War 1 (1914 1918) in the detection of enemy submarines. It is impossible to condense into one short article all the credits and honorable awards due this distinguished inventor.

"I AM YESTERDAY AND I KNOW TOMORROW" Reginald Aubrey Fessenden October 6, 1866 - July 22, 1932 (Lived in Fergus, Ontario) Reprinted

from: THE CAT'S WHISKER

|

Several

years prior to his first broadcast by radio, Reginald Fessenden had perfected a new method

of sending Morse code more effectively than Guglielmo Marconi. To him goes the credit for

successfully transmitting the sound of the human voice between two 50-foot towers on Cobb

Island located in the Potomac River, Washington D.C., December 23rd, 1900.

Several

years prior to his first broadcast by radio, Reginald Fessenden had perfected a new method

of sending Morse code more effectively than Guglielmo Marconi. To him goes the credit for

successfully transmitting the sound of the human voice between two 50-foot towers on Cobb

Island located in the Potomac River, Washington D.C., December 23rd, 1900.  This historic first message was:

"One, two, three, four. Is it snowing where you are Mr. Thiessen? If it is, telegraph

back and let me know." So, at Cobb Island on December 23rd, 1900, for the first time

in the world's history, intelligible speech was transmitted by electromagnetic waves. Thus

the honour of taking the first step in the development of what is now universally termed

'radio' deservedly belongs to Reginald Aubrey Fessenden.

This historic first message was:

"One, two, three, four. Is it snowing where you are Mr. Thiessen? If it is, telegraph

back and let me know." So, at Cobb Island on December 23rd, 1900, for the first time

in the world's history, intelligible speech was transmitted by electromagnetic waves. Thus

the honour of taking the first step in the development of what is now universally termed

'radio' deservedly belongs to Reginald Aubrey Fessenden.

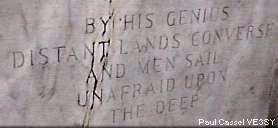

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden, this great man who gave to the world so much yet received so

little, died in his home by the sea in Bermuda on July 22nd, 1932. Burial was in St.

Mark's Church cemetery and over the vault was erected a memorial with fluted glumns. On

the stone lintel across the top were inscribed these words:

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden, this great man who gave to the world so much yet received so

little, died in his home by the sea in Bermuda on July 22nd, 1932. Burial was in St.

Mark's Church cemetery and over the vault was erected a memorial with fluted glumns. On

the stone lintel across the top were inscribed these words: